By Steve Black and Phil Dering

Eagle Nest Canyon in the winter is a far cry from the summer, when archaeologists usually work in the region. Instead of stifling back-to-back days over 100 degrees, winter conditions are a lot cooler, obviously, but strikingly varied. Some days it is sunny and balmy t-shirt weather by mid-day with a highs in the 70s and low 80s; a sheer joy to be alive and working outdoors. But then windy northers hit and daylight temperatures don’t get out of the 30s or 40s it’s not quite as joyful; but, walking through the canyon is still quite delightful provided you are layered up. On a recent morning I (Steve) was joined by Phil Dering, an archaeobotanist with advanced training an experience in both dirt archaeology and in analyzing the plant remains found in the dirt. He is also a paleoethnobotanist, meaning he tries to understand how the people who lived in the canyon for so many generations used and understood the plant world. If the topic interests you, take a look at the online exhibit called “Ethnobotany of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands” that Phil and I put together several years ago: www.texasbeyondhistory/ethnobot/. To be clear: Phil is the plant expert, Steve is just wordy.

Back to that morning in the canyon. As we followed a trail leading down that meandered along the base of the cliff we passed through a long and tall, but very shallow, overhang known as Horse Trail Shelter. Phil stopped to point out two evergreen bushes from the buckthorn family that both held a surprising quantity of mature and immature ‘berries’ (technically fruits). This is winter, why do we see hanging fruits—these are supposed to be harbingers of summer and fall? Their presence in early February points to a peculiar aspect of the Lower Pecos: for many desert plants seasonality is strongly conditioned by climate. Late summer and fall of 2013 were unusually wet, allowing some plants to bloom and put on fruit far later in the year than they would have in “normal” conditions. While this makes it difficult for the archaeobotanist to make confident seasonality assessments based on charred seeds found in archaeological sites, such atypical years must have been a boon for canyon dwellers.

The two kinds of berries also tell another cautionary tale: foragers must know their plants. The biggest berries of the two, and far more common, were those of coyotillo. This small, evergreen shrub with deep green, almost glossy and distinctively veined leaves produces green fruit about ½” across that ripens to a dark purple-black color. While the sweet juicy outer pulp of the dark purple ripe coyotillo fruits might be edible, the large seeds within contain deadly neurotoxins known to have poisoned livestock and people, tragically mostly unsuspecting children. To learn more read www.texasbeyondhistory.net/ethnobot/images/coyotillo.html.

The other berried bush growing in the same area is condalia, a spiny evergreen bush that produces abundant crops of small purple-black fruits readily eaten by wildlife and humans. Its berries are half the size of coyotillo fruits, and most of them weren’t ripe, but the dark purple almost black ones were surprisingly juicy and tasty. In fact, birds and other critters had stripped most bushes bare. To learn more read www.texasbeyondhistory.net/st-plains/nature/images/condalia.html. Condalia fruit couldn’t have been harvested in sufficient quantities in the winter for much sustenance for native peoples, but they would have been a quite welcome dietary supplement. Edible fruit in the winter canyon, who knew?

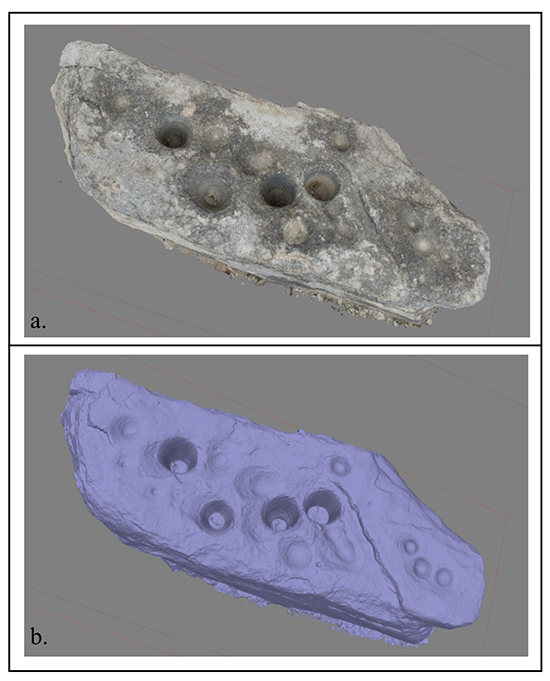

Back to Horse Trail Shelter. After we stopped to talk berries, we took a look at several limestone boulders which fell off the cliff many centuries ago. Long ago native plant processors turned these flat-topped boulders into amazing workstations for grinding, pounding, pulverizing and otherwise processing plant foods, especially seeds, nuts, and beans. The boulders are covered by unnatural depressions often called “bedrock mortars.” The tops of these particular boulders had been freshly exposed and cleaned up picture pretty by Texas State graduate student Amanda Castañeda last month during her winter break between semesters.

Amanda is taking on the topic of bedrock features for her Master’s thesis research. She spent several days working at the site to help develop her documentation methods. As her photo shows, the bedrock ‘grinding’ features come in different sizes and shapes, some being obvious deep mortars but others include shallow cupules that might have served to hold nuts for cracking? How does one tell what was being processed in which kind of hole? Amanda hopes to figure this out through a combination of a comparative study of ethnographic accounts, and thorough documentation of ‘bedrock mortar’ sites in different settings including measuring hole morphology, looking at wear patterns in the best preserved holes, and maybe even getting a residue expert involved. But that is a story we hope she will tell as her research progresses.

In winter the canyon walls protect the plants a bit better than those in the nearby uplands. Even so most plants are brown and leafless, although others like the berry plants are still green as are the mountain laurels. Most winter days the birds are not as active as they are during other parts of the year, but on warm calm days the ravens, wrens and others make themselves known. On a recent afternoon Steve hiked back down into the canyon after the dig day was over and enjoyed the solitude, soaking up the winter sun, listening to the birds, and watching for movement. You can see the topography better sans leaves, and the sounds seem to carry farther on calm, crisp days.

Some winter days are less enjoyable. Two weeks ago we experienced three overcast and windy days in a row that did not get above the low 40s. No matter how many layers you have on, after hours of cold wind swirling up the canyon and down your neck, clutching cold metal tools, and kneeling in one spot for too long, winter sinks into your bones. You even catch yourself thinking fondly of a hot summer day. Happily the bone-cold days aren’t constant and most afternoons are quite tolerable.

We do find ourselves repeating the observations and speculations each generation of Lower Pecos archaeologists has made about rockshelter orientation. Eagle Cave gets early morning sun, but by noon it is back in the shadows, and the rockshelter (being wider than it is deep, it really isn’t a cave) seems to catch the wind no matter which direction it is blowing from. Skiles Shelter, on the other hand, is in full sun from late morning onward – we have to use shade tarps and are down to t-shirts on many afternoons when elsewhere in the canyon requires additional layers. These experiences lead us to speculate – “this shelter must have been a winter favorite,” or “no way they would have lived here in the winter” and so on. But how do you actually find hard evidence of seasonality when sometimes even the warm weather indicators are ripe and harvestable in the winter?

For us, the 2014 winter in the canyon is a lifetime experience we will likely tell glowing stories about for the rest of our careers. Then again, at day’s end we go back to camp and enjoy a hot shower, a good meal, and a warm bed. Those who spent the winter of 2014 B.C. here might not have been quite so enthused.

Pingback: Winter in the Canyon: ASWT Project Blog | Mary S. Black

With the presence of the ‘bedrock mortars’, has any evidence of agriculture been found, or were these people strictly hunter/gatherers?

Hi Richard. Based on what we know at this point in time the peoples who lived in the Lower Pecos were hunters and gatherers for the entire span of human occupation (+/- 10,000 yrs). Even though agriculturalists were only a couple hundred miles away, no evidence of agriculture has been found out here.

Pingback: The Archaeobotanical Team Forms | Ancient Southwest Texas Project - Texas State University